Break the Digital Monoculture

INTERVIEW WITH MOREHSHIN ALLAHYARI

We need to break the digital monoculture and challenge Big Tech in their relentless drive to transform our digital environment in its own image. Digital Earth conducted interviews with artists, technologists and activists, who work towards building a pluriform and inclusive digital environment. Our main question: How can we break the digital monoculture and build a more humane digital future?

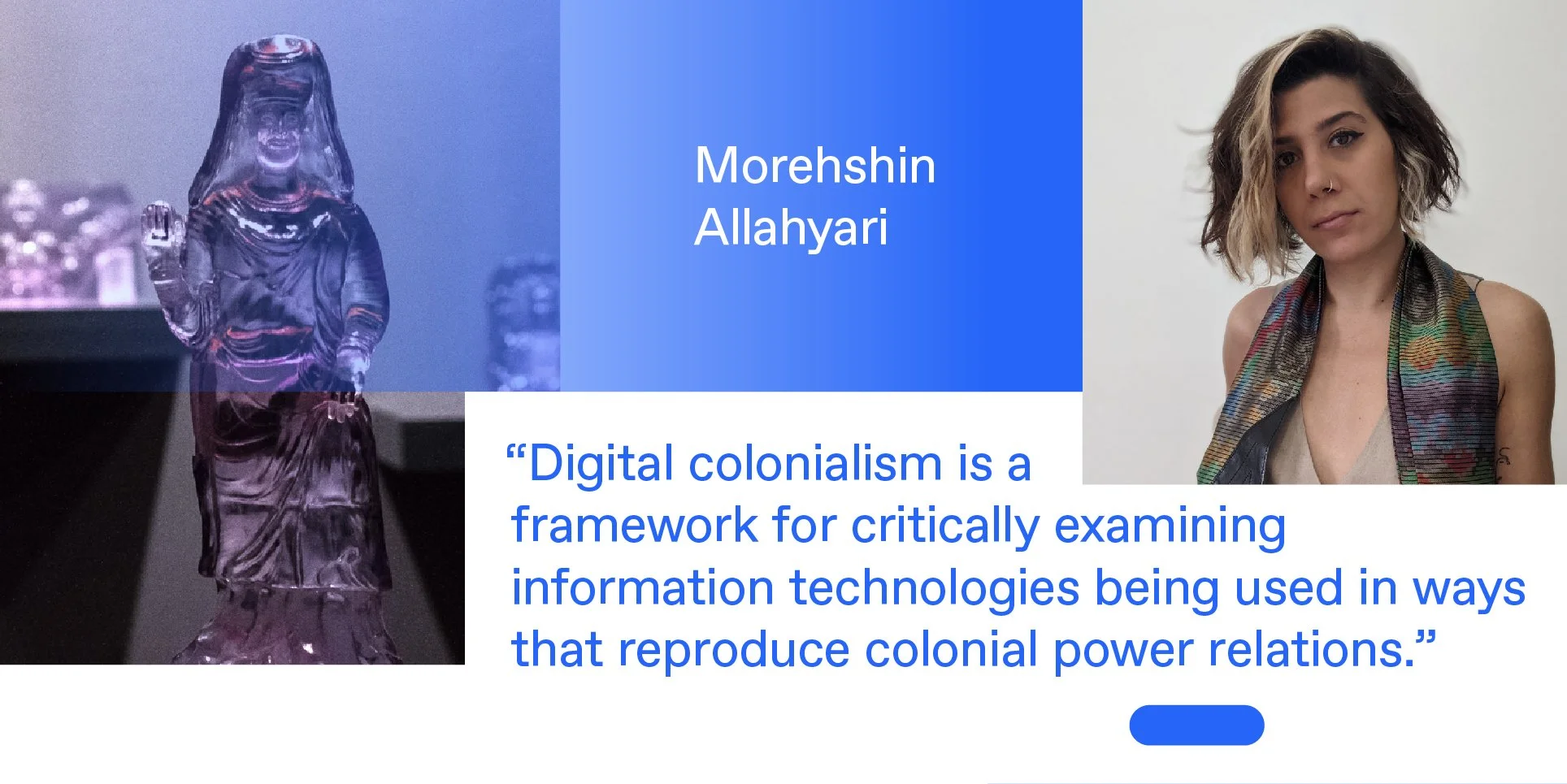

Morehshin Allahyari, Material Speculation: ISIS – Ebu, 2015-16, 3-D printed plastic resin and electronic components. Courtesy of the artist.

Morehshin Allahyari (Persian: موره شین اللهیاری; born 1985) is an Iranian-Kurdish media artist, activist, and writer based in Brooklyn, New York. She uses computer modeling, 3D scanning, and digital fabrication techniques to explore the intersection of art and activism. Inspired by concepts of collective archiving and cultural contradiction, Allahyari’s 3D-printed sculptures and videos challenge social and gender norms. She wants her work to respond to, resist, and criticize the current political and cultural situation that is experienced on a daily basis. Her work has been part of numerous exhibitions, festivals, and workshops at venues throughout the world, including the New Museum, MoMa, Centre Pompidou, Venice Biennale di Archittectura, and Museum für Angewandte Kunst among many others. She is the recipient of United States Artist Fellowship (2021), The Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant (2019), The Sundance Institute New Frontier International Fellowship, and the leading global thinkers of 2016 award by Foreign Policy magazine. She has been awarded major commissions by The Shed, Rhizome, New Museum, Whitney Museum of American Art, Liverpool Biennale, and FACT.

Read more here.

In your practice, you combine art activism, digital fabrication, digital art and memory with a specific focus on West Asia. Could you tell us more about your background and how you arrived at this exciting mixture of exciting fields?

My entrance to the art world was through creative writing. As a teenager storytelling was something that I became really interested in and the ways that I found power and in ways of expressing things, starting from personal experiences and then arriving at collective experiences.

In Iran, where I grew up until I was 23, I studied social sciences and Media Studies. You can see traces of that in my practice in that art making is not just art for art's sake, and it's not just technology for technology's sake. Rather, my work reflects how different social, political, cultural issues and topics are expressed. I then choose the relevant medium or technology to convey a message to make something that is invisible, visible.

Being in school in Iran and also just like the life that I was interested in even as a young adult also had an influence on the way to look at the world throuh like critical eyes; not in terms of negativity, but like rather always like asking questions and never taking things for granted and never accepting ones status quo.

When I came to the US for graduate school, I studied digital media studies for my MA and new media art from my MFA. That's where I became interested in technology. We had one class, which was an elective class that was called cyber studies, and there I fell in love with these ideas of thinking about the web and internet and cyberspace critically. My thinking about social issues and political issues kind of came together in one place. And then technology became a toolset that then carried those points.

What is the main question you are fascinated by at this moment in time?

In my practice, for the last six or seven years, I have been really interested in this non-binary relationship between history and technology. I say non-binary because I don't see them as things that are against each other necessarily. For me it's a much more complex relationship between these things.

In my work, for example through Material Speculation ISIS (2015-2016) and She Who Sees the Unknown (2016-), I've been interested in looking back into the past to bring out things, situations, or in relationships with it that hasn't been considered. I call this refiguring or re-figuration and I wanted to re-reimagine ways of thinking about now and the future with a focus on the Middle East or Islamic culture.

I have also thought a lot about archiving as an art practice; such as 3D printing, digital fabrication, being a method or a tool for archival work. Or more traditional ways of thinking about archiving documents, such as PDF files and images. I am now questioning access to archives and questioning open source.

This has a lot to do with how I want the world to be in terms of how creatives and artists practice their work. Artists that are always looked up to are people that go beyond their artwork. It is people that are generous and not interested in their practice with this idea of “Oh, I'm just going to be in my studio solo and make work.” Rather making becomes about something bigger, be that community building, or giving access to their research, or even being open to sharing a process.

Morehshin Allahyari, Dark Matter (First Series): #pig #gun, 2013, 3-D printed plastic resin. Courtesy of the artist.

What are the key issues of Digital Colonialism?

Digital colonialism is a framework for critically examining the tendency for information technologies to be used or deployed in ways that reproduce colonial power relations. But my research is also connected to cultural heritage and historical heritage.

In Material Speculation: ISIS series, I reconstructed 12 artefacts that were destroyed by ISIS in 2015 at a Museum in Iraq. I was doing reconstruction work but the product had many layers to it. The sculptures had a memory card and flash drive embedded into them. When I did that project in 2015-2016, ISIS was at the height of their power. They had an intense presence on social media.

Simultaneously, on the technological side of things, we have this sudden rise of 3D printing. I was also living in San Francisco, where there is a really crazy presence of tech companies. Suddenly, all of them started to buy these tools, and travel to different parts of the Middle East or different countries in Africa, to scan artefacts that were at risk of being destroyed.

I became curious because in a lot of time, we will have the issues of monopoly of information. The companies will have copyright ownership of these scanned artefacts to a point where even if, for example, the Lebanese government wants access to a certain object from their national collection, they might not be allowed.

This was a moment when no one was questioning what was happening to this digital data. If you go to the British Museum or MET Museum, we can see the colonial power by simply asking how certain objects even got there. But with digital digital practices, it's a much more grey or unknown area. I really wanted to talk about what digital ownership means in this way? That also played a really important role in the way I as an artist started thinking about access to or protection of knowledge and cultural heritage of your country.

You have also been looking at the relation between digital storage and archiving in relation to human memory. Could you elaborate more on this relationship

The first time that I saw an object getting 3D printed, I was blown away by watching this process of something being transferred from the digital to the physical. Now that’s normal, but back then it was so science fictional.

The first thing I thought about was what would happen if I had access to a 3D printer in Iran and printed things that are forbidden. In the series Dark Matter (2014) I extended this thought into ideas of archiving things considered ‘dirty’ as an archiving and documentation practice. This series was focused on reproducing objects that had been censored in Iran at this time.

In Material Speculation: ISIS series the sculptures were like time capsules because there were the elements of the memory cards and flash drives inside the body of the artefacts. Inside the flashcards and memory card there are PDF, files, images, my email correspondence with historians, scholars, the process of making the work, as well as OBJ, STL files of all the artifacts.

At that point, I wanted to keep or hold this knowledge for future civilisations. It is a poetic, political, and practical gesture. Because in the future, even if you have access to this data, there's no way to replace what was lost, although you can reprint all the artefacts. But they would serve as a point of memories, some kind of resource for knowing what was there, what was lost, and what it looked like.

Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown, 2016,

HD digital video. Courtesy of the artist.

In She Who Sees the Unknown, you also extensively focus on mythologies particularly the monstrous and dark goddesses. Why are you working with these kinds of figures?

In She Who Sees the Unknown I'm going back and looking at mythical female/queer figures, and how their stories have been forgotten and underrepresented and then building objects with them.

Growing up in Iran and reading mythical stories it was always about male figures. Naturally I began questioning where the female figures were. What are the figures that I can focus on or think about where they have this potential in them to become vessels for storytelling for refiguring and for rebuilding other worlds?

Jinns became specifically important because they are so present within West Asian culture, South Asian cultures, and also African Cultures. And also they're spoken of in the Quran as creatures that are hybrid, they're shapeshifters. I felt like it was a figure that was not explored, and there was so much room to think about it so I wrote new stories about all of them.

You just released the archive from She Who Sees the Unknown, could you tell us more about that decision and how it came about.

The archive is a result of four and a half years of research into She Who Sees the Unknown. The research involved going through so much archival material. But a lot of the time it was hard to get access to certain manuscripts because of the gatekeeping of the Western based institutions. They wanted me to sign contracts to download materials from my own culture. This became frustrating and annoying.

When the project was coming to an end, I wanted to release this archive I had collected, but obviously I wanted it to be curated. In the archives there are like 40 rare manuscripts. It became important to share the material and those resources. When I was building the platform, I wanted to bring in some of those thoughts around digital colonialism to turn around those power structures.

So in thinking about open source, I had to question whether open source is inherently positive. The answer is obviously no. It's important to question where it is that you are sharing information and what platforms you are giving this information to within the imperialist, colonialist systems. In seeing how I could turn around power structures, language became key.

On the archive’s website, you can have access to the first layer of the archive but to have access to the second, third, and fourth layer, you have to know either Farsi or Arabic to put in certain codes. I worked with hackers and designers to develop it and it’s almost impossible to gain access via a translation app. As you go deeper into the archive, you access the more rare and harder to find material.

It's honestly been like an experiment, and I was very afraid that people would be angry. But it was really important for me to be intentional about who you give access to and why you give access to a very specific demographic and how to protect some heritage that has constantly been re-appropriated and taken over and owned.

To continue on your last line of thought with regards to this shared digital future and its collective practice, could you propose an icon or a symbol or a monument for a digital future?

That's such a good question and a very difficult one. It would probably be Huma, a jinn, who brings the fever and heat to the human body.

I extended that to the climate crisis, and also when I tell the story it is connected to how we experience a crisis. So when there is a crisis, we will all experience it equally and evenly, without the notions of class, race, or geographic location. That’s the figure for me that is the representation of an ideal, utopian world. Kind of like utopia through dystopia.