Break the Digital Monoculture

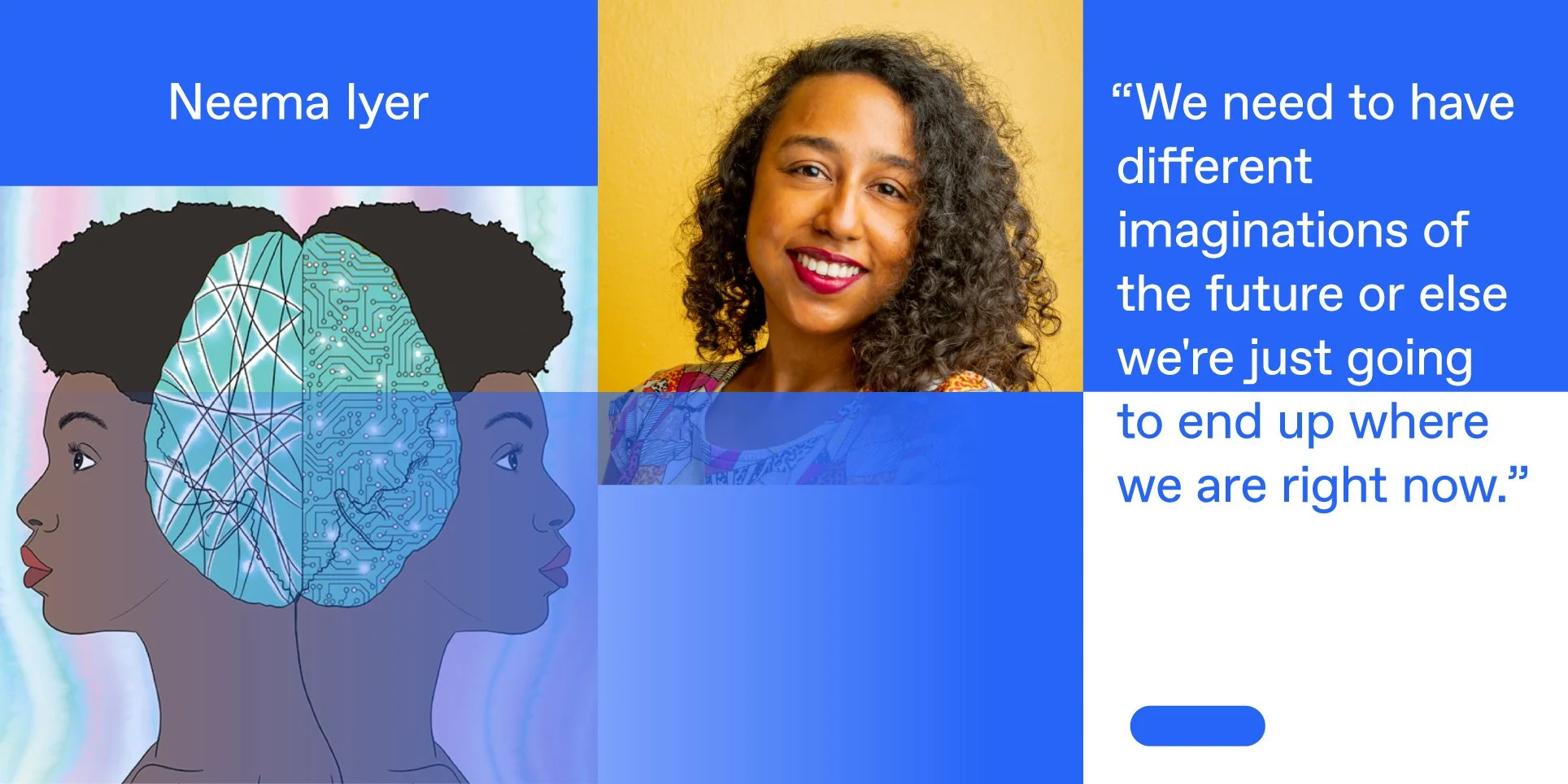

INTERVIEW WITH NEEMA IYER

We need to break the digital monoculture and challenge Big Tech in their relentless drive to transform our digital environment in its own image. Digital Earth conducted interviews with artists, technologists and activists, who work towards building a pluriform and inclusive digital environment. Our main question: How can we break the digital monoculture and build a more humane digital future?

Neema Iyer, Amplified Abuse, 2021. Courtesy the artist.

Neema Iyer is an artist and a technologist. She is the founder of Pollicy, a civic technology organization based in Kampala, Uganda and is a co-host on the Terms and Conditions podcast. She currently leads the design of a number of projects focused on building data skills, on fostering conversations on data governance and digital security, and on innovating around policy.

Read more here.

You are working at the intersection of digital rights, data governance, and feminism. How did you arrive here?

I've always been drawn to the arts. But when you live in Africa, artists aren't really appreciated as significant contributors to society so I decided to pursue a career in medicine, but I switched and I did public health for my Masters.

Thereafter, I got a job with a think tank where I looked at mental health and the use of technology. Afterwards I moved on to an interactive voice response company because I was starting to question the efficacy of text as a medium to communicate with people. I moved to more voice based work because there is more flexibility in terms of using local languages and you know, playing around with voice and music. And then from there, I just saw that there was this big gap in data and digital literacy more broadly.

Therefore, I started Pollicy in 2017 which focuses on digitalization with governments and with civil society. At Pollicy I found that there was a big gap in terms of how we talk about data and digital spaces. There’s a lot of jargon which makes it very inaccessible for a large proportion of people.

I've always been a feminist and grew up with those ideals. The more I studied these spaces, the more I realised that there is a very significant gender digital divide. For reasons such as costs, safety, access, education, skills, and patriarchy, among others, women are not getting to use data and digital platforms in the same way. This was where we saw the need to bring in this gender element that if you just apply a one size fits all, it's not gonna work. So that's how technology and feminism came together.

What is the main question that drives you at the moment?

This sounds cliche, but I'm just always driven by this need for social justice. I do feel like, on one hand, that digital tech has the ability to transform people's lives in terms of improving their life experiences and how they interact with governments, how governments provide services, how you receive education, how you receive entertainment, and how you work. And with remote work now becoming much more than the norm, this is an opportunity where before you wouldn't get hired for a job because they wouldn't sponsor your visa to go to the US or the UK. But now you can be where you are and get a good salary.

Even if you think about feminism just a few years ago, you couldn't really talk about these issues. From when I joined Twitter about 10 years ago to now, the conversation has moved so much. No matter what people say, social media can change things with the way campaigns are run on Facebook, the way people organize movements, and it's really incredible to see what is possible. But on the other hand, you know, we're also very aware of what the threats of big tech are and how technology can be also oppressive in nature.

We're just having a conversation about how much AI is such a buzzword, but nobody really knows what it means. But the fact is they do have real consequences on people's lives. Automated decision making is deciding on giving social services or even to grant visas. Of course, that's not as much happening in the African context.

I feel like we're at a point where we can determine what our future looks like instead of waiting for other countries to come up with harmful tech that is then imported to Africa. Maybe we can decide what we want, what kinds of technologies we actually want to know, and what kinds we don't want, and work from there.

Neema Iyer, Automated Imperialism, Expansionist Dreams, 2021. Courtesy the artist.

Recently, Pollicy published a report on digital extractivism specifically focused on the African continent. What is digital extractivism and it's history on the African Continent?

We wanted to look at how colonialism is still present. Latin America, Africa, and Asia had a lot of natural resources which were extracted and taken by colonial powers. At Pollicy we wanted to ask the question, “Do technology companies work in a similar manner in today's context?” We created a list to show that some of these practices are still being used today. So for example, a lot of African countries do not have data protection laws, or if they have them, they're not really implemented in any realistic way.

Therefore these states become an opportunity lot of data mining. And a lot of these companies don't pay any taxes. So one of the statistics that we had showed that the tax avoidance that happens on the African Continent is more than the amount of aid that the continent receives.

Another thing we found is that you'll often see these ‘tech for good’ initiatives which often launch programs first in Africa. These technologies are not tested out anywhere else. 95% of them fail, for one reason or another, and sometimes it can be quite harmful.

For example, there was biometric testing in refugees in Ethiopia and they didn't really have an option to say no. The company might say that it was consensual. Yet, if you didn't say yes, then they didn't get food. That’s really concerning and you'll see it across the board. It'll be like blockchain for refugees or AI for migrants; very exploitative types of programs that they test on very vulnerable people. The companies come to Africa, they'll run a project for two years, and then we'll just never hear of them again.

How does one counter these developments? What is the role of governments, big tech, and civil society in this regard?

One of the things we thought about is how unions can work in terms of digital platforms. For example, with remote work you can be based anywhere. But then you often hear people say, like, “Oh, well, you're in Africa, so I'm going to pay you 1/10 of what I would pay somebody in the US or Europe.” I think it'd be interesting in that sense to ask what kind of agencies exist to protect them as workers?

When we did this research we found it difficult to find sources. And even when we did find sources they would be from questionable companies. These institutions are way better funded than academia. So that's kind of all you have to rely on.

With governments, there's a need to create more progressive laws. So I do think a lot of countries just tend to over-regulate. And they tend to be very punitive in nature. So if you have a data protection law, and it is broken you pay a fine. But then what are you putting in place to assist companies to become compliant? As of now there's no such program in place.

Governments have to step up and really focus on what society in 10 years look like? They're regulating a society that existed five years ago. As for big tech, I think it's a matter of just continuing to do research and put pressure on them. I think it's a lot of research that needs to be done to hold these companies accountable.

Neema Iyer, Engendering AI, 2021. Courtesy the artist.

You have previously spoken of the experiences of African women in online spaces. What is it that we can learn from African feminism and its view on technology, to build a more hopeful digital future?

I think this ties back to the previous point that we need more research, because technology is often built with detrimental biases. The only way for us to get our needs out there is to do the research and have these conversations. That guided the Afrofeminist Data Futures project which we did at Pollicy.

Oddly enough, this project was funded by Facebook, and they had a call to see how feminist movements in Africa use data. But it was such an interesting topic that I'd always wanted to work on. We got to talk to about 40 feminist movements, and really ask them about what their data and digital needs are. And basically, many feminist movements are lagging behind in terms of how they use data, how they're represented online, and how they see the future of tech.

Most importantly, there is a lot of distrust. Black and brown people are discriminated against on these platforms. Recently on Tik Tok, if you wrote things like “black lives” or anything similar to that, you got censored. But if you did the same for “white lives,” there were no issues. People basically have a distrust of big tech, because they don't respect us as people.

I think there's many different ways people can understand feminism. I think some people would say feminism is equality, right. But that doesn't really make sense because human beings are not equal at all. So I think for me, I really think of feminism as the freedom to really live your life in the way you want. To live it free from fear and to live it in a way where you can make the most of whatever opportunities are out there.

From that angle, it really makes sense working on digital needs, because digital platforms really do give you that freedom because on online spaces you can be anyone and you can do anything. But I also understand feminism as based on love, care, ethics and appreciation of things like arts and labour. So that's kind of how my feminism comes into thinking about technology, and hoping that big tech and governments can also become a part of this grander ethos.

Do you have examples of initiatives that are driving this feminist technologies for change and care?

The US has a cultural hegemony on the world, they have developed many of the platforms we use today. There's so many things in my childhood that were based on American culture that I had never experienced, but you feel like you've experienced it, because you've seen it so many times. But now with digital platforms, it's become even more severe.

I heard that children across Africa are starting to have American accents. Everyone speaks like Americans, they pick up their cultural trends, they eat what Americans eat, the restaurants change to suit whatever is in the hipster Instagram photo. Even the kind of scifi speculative fiction books are American.

And that's why when I saw artist Dilman Dila’s work, it felt so refreshing, a different perspective. And those are still so so, so rare, where you can find, you know, good writing that talks about speculative fiction. We need to have different imaginations of the future or else we're just going to end up where we are right now. We're in the future that the US built. And we'll always be stuck in it unless we can think about something different.

I think the current ways in which we organize and use the data also leads very much to a digital monoculture. I think one of the big problems with the internet right now is that the entire internet is ad revenue based. And I think that that is the root cause of all evil.

In regard to this, I do feel like what this company COIL is trying to do is quite interesting. You just pay people and websites based on how long you're on their page. And so like, one month, maybe you have a budget of like, 10 euros, and then they just divide that 10 euros based on your browsing history for the whole month. It’s very automated and you don't have to think about it. I know, in China they have this service where you can directly give content creators money. Now, on Twitter you can tip people.

That is a whole different economic model of running the internet. And it's one that I would totally be down for. I want content creators to be rewarded for the work. I don’t want advertisers and all the middlemen advertisers to get money.